I often joke that one of the reasons why I’ve been alone more than I’ve been in relationships is because I’m an only child and a Leo and that means I never learned how to share. That Barbie townhouse and 3-speed bike with the banana seat from childhood were ALL mine! Sure, it makes for a good quip and there’s an element of truth to it, but not in the self-centered, spoiled way that it sounds. For me, being an only child and a Leo means that I prefer to handle things myself and not ask or bother anyone for anything. It’s a pride thing. In fact, in relationships I have a tendency to take on more responsibility for my partner’s well-being than I do for my own. But, that’s a blog post for another day. Or not.

Today marks two years since my mother’s death and I’ve been ruminating about all the ways I didn’t handle things like I now wish I had. I never put an obituary in the newspaper. Why, you may be asking? Well, I didn’t want to put anything in the paper until I knew when I was having a Memorial Mass. Mom had decided to spare me the stress and pain of a full-tilt rosary and funeral and instead allow me to schedule a Memorial Mass at a later date when I was ready. I doubt she thought she’d still be waiting for that Mass two years later, or to be buried, for that matter. (Her ashes are still in the dining room.) I told myself that I had to wait to schedule the Mass until I could afford to have some sort of after-Mass luncheon for people. (Catholics love a good post-funeral feed.) Being unemployed for four years as Mom’s caregiver meant that money to throw a party wasn’t something I imagined I could swing. So logically, no money = no party = no Mass = no obituary. It made sense to me at the time, but now, I just feel guilty. Intellectually, I know that Mom isn’t concerned about an obituary or a Mass or a party at this point. I’m not so sure about the ashes on the dining room table, however…

As I am wont to do, I started looking for deeper meaning behind these post-death decisions. That’s when the idea of not learning to share came to mind. I realized that what I hadn’t been willing to share was grief. I’d been protective of my grief. In a weird way I felt resentful that anyone else would get to share in that grief via an obituary or a Mass, or a party, or at the gravesite. No one shared in the daily stress, sacrifice, pain, and sadness during the years of being a caregiver. That was all mine. I wanted the grief for my mother to be all mine as well. I earned it. I know this may sound illogical or immature, and truly, I know just how many people loved my mother and were blessed by her presence in their lives. Part of me thinks that I deprived them of the opportunity to engage in communal grieving and I feel bad about that. At the same time, it hit me that I’ve spent my whole life doing things for other people’s approval, comfort, and benefit. My approval, my comfort, and my benefit were always an afterthought. These last two years have been an exercise in discovering what I think, what I believe, what I feel, what I want, and what I need. It hasn’t been easy, but it has been revelatory.

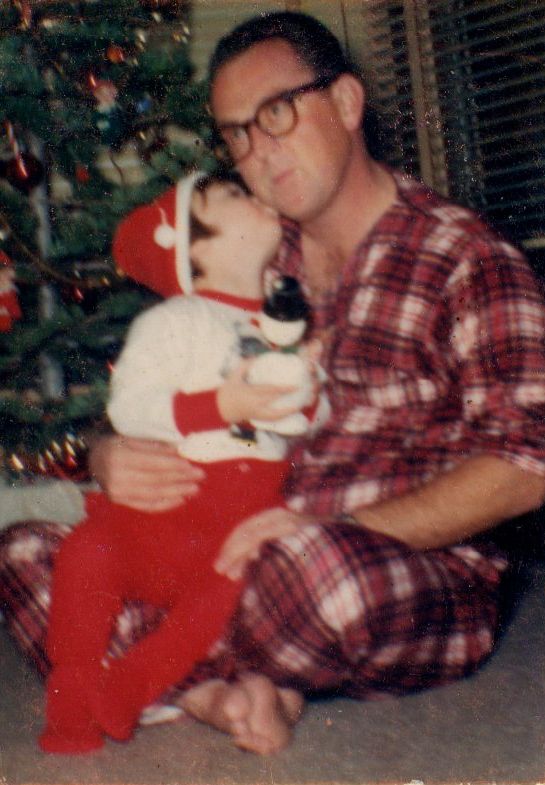

If I still had that Barbie townhouse or that bike, I would share them. But, they are long gone. However, I can share this commercial for the townhouse and this photo of me on that bike on Christmas morning in 1970:

I can also start sharing my thoughts, my feelings, my stories, and my vulnerabilities more openly. That’s a start.